The draft report itself is quite brief, and shall be broken down into its respective headings.

Exclusive Rights

Ms. Reda, although a supported notion by many, does not want to eradicate copyright altogether. Copyright is an important decide to incentivize and reward independent, original creation, and this writer for one would never want to see it wholly removed from the world's IP scheme. Ms. Reda does, however, bring an interesting addition to this existing regime: "...[she] calls for improvements to the contractual position of authors and performers in relation to other rightholders and intermediaries". One can try to envision how, through law, the relationship between creator and funder could be improved, seeing as the relationship is (often) quite unbalanced by its nature. In the UK the freedom of contract is a corner-stone of contract law, and should be upheld, even if/when it has the capability to produce unbalanced contractual relations. This, by no means, should lead to unfair contractual terms, but it does not present a need for legal intervention in the scheme of copyright in itself.

A big point of contention within copyright has been fair dealing, and the allowance of using copyrighted material for the purposes of creating new, original works, or simply for the reporting or discussion of current events. Ms. Reda proposes that "...the EU legislator should further lower the barriers for re-use of public sector information by exempting works produced by the public sector - within the political, legal and administrative process - from copyright protection". In the UK at least, under the Re-use of Public Sector Information Regulations 2005, the use of such information is allowed under certain circumstances, and only through the consent of relevant governmental bodies. Although by no means perfect, it aims to safeguard potentially sensitive information from public viewing, even if requested through the Freedom of Information Act 2000. Ms. Reda's objective clearly is one of openness and freedom of publication for all; however this would present challenges if implemented with little or no restrictions.

| When piracy failed politics was what was left for Captain Hook |

Exceptions and Limitations

Exceptions, especially when it comes to private use of copyrighted content, have been a sore subject for a lot of parties involved. Too little allowance of use restricts the freedom to use your legally purchased materials, yet too few restrictions can lead to mass abuse of said content. In that vein, Ms. Reda has proposed major changes in this area, which should be addressed alongside the above.

Ms. Reda proposes that "...exceptions and limitations should be enjoyed in the digital environment without any unequal treatment compared to those granted in the analogue world". Arguably, this approach is very sensible, and this writer for one cannot think of an instance off the top of his head where digital would be excluded from exceptions when compared to its analogue counterpart. Nevertheless, this is something that should be enshrined in the back of any law pertaining to modern copyright, and defended to ensure the comfortable transition from the physical to the digital in the years to come.

She further proposes that "...all exceptions and limitations referred to in Directive 2001/29/EC [should be made mandatory], to allow equal access to cultural diversity across borders within the internal market and to improve legal security". This writer would argue that the introduction of exceptions is less about diversity, but more about the promotion of communication and the creation of new, potentially copyrightable, works. Whether all exceptions should be made mandatory is a question one cannot easily answer; however, quoting many parents, too much too quick can be bad, and a gradual introduction would be beneficial in the long run. Ms. Reda also wants to add more flexibility to the aforementioned exceptions, and her argument echoes that of US and Canadian fair use where the exceptions are less à la carte, and more malleable to a different assortment of uses based on the use and their impact on the original works.

Hyperlinking is currently the topic of choice at the ECJ, and Ms. Reda also proposes its protection, due to a lack of communication to a new public through hyperlinking. As has been discussed in both Svensson and BestWater, the ECJ seems to quite firmly protect this notion in Europe, and with the forthcoming decision in C More hopefully even further clarifying this, this write does not fret for the sake of hyperlinking in the near future.

Ms. Reda also suggests that "...the exception for caricature, parody and pastiche should apply regardless of the purpose of the parodic use" - something that this writer will wholly disagree with. Deckmyn was the most recent instance where parody was assessed on an EU-wide basis, and the purpose of use in terms of parody is an important consideration and should not be omitted. A borderless approach to parody will only create abuse and infringing works created under the veil of parody when no parody was intended. When using copyrighted works the use should be a genuine, bona fide parody use, which both protects expression and encourages it through creativity in parody and thus, potentially new protectable works.

Ms. Reda goes further into other exceptions, but for the sake of brevity, those will be left out, although still remain important considerations for the future.

Conclusion

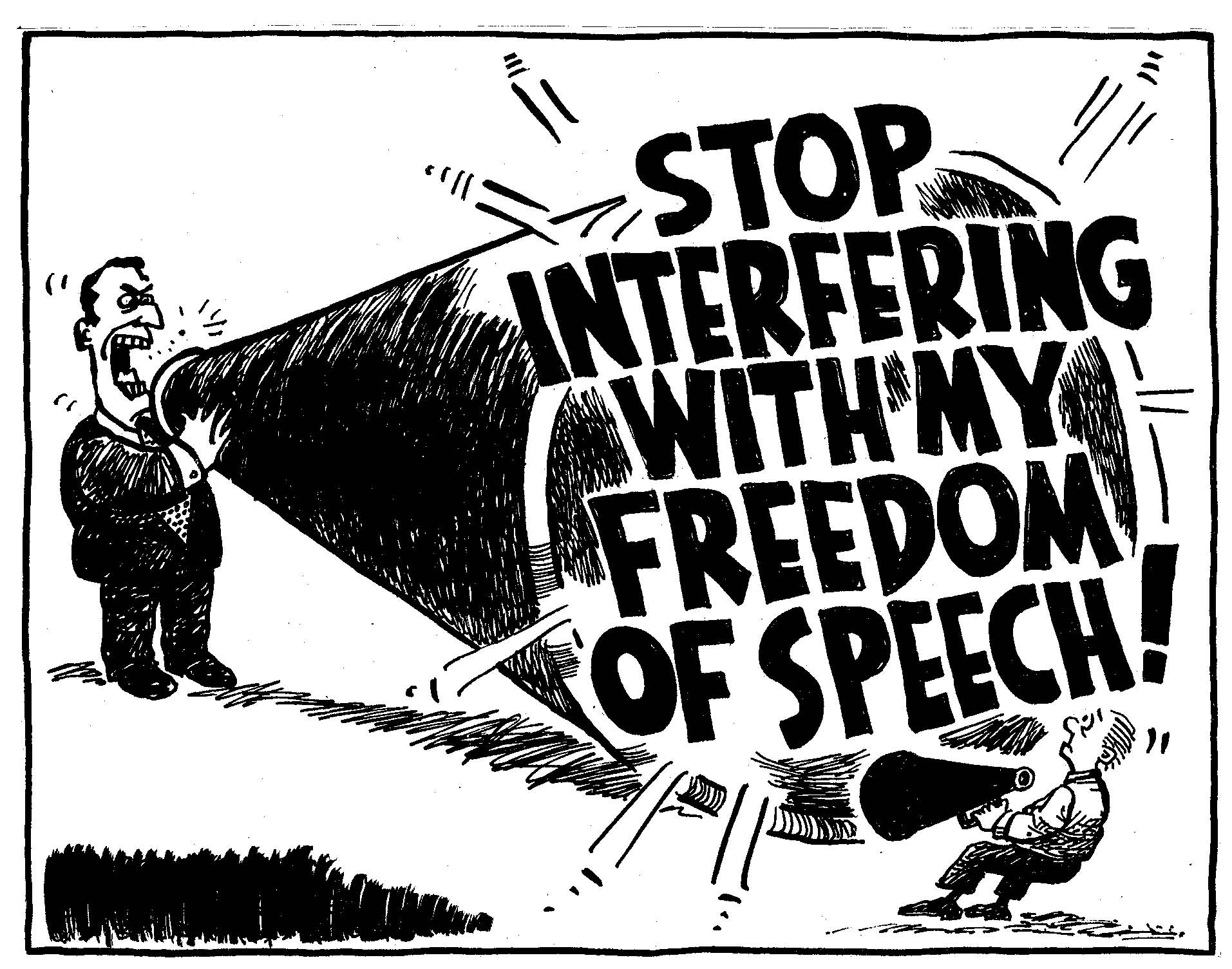

The response at large to the proposal has been varied, and that's no surprise. What Ms. Reda is proposing is by no means revolutionary, and a lot of what is brought up, from an IP person's stand-point is worth protecting and/or extending copyright to in its little realm. Yet, what Ms. Reda's undoing is, is her affiliation with the Pirate Party. The image evoked to anyone involved in IP, especially rights holders, will be one of dismantlement, and a fear of the allowance of piracy and losing the very structure your livelihood depends on. Ms. Reda does not propose this; however she inevitably loses out on that one simple aspect: public relations.

This writer commends a lot of what she has put forth, and seeing how copyright has started to evolve in the last couple of years yields a tremendous amount of promise. Nevertheless, there are doubts as to the proposals and their efficacy in the future, but from an end-user perspective, Ms. Reda gives a glimmer of hope for a more open (i.e. less restrictive) copyright regime, which still aims to support the content creators out there and protect their works.

Source: IPKat