The case of Simba Toys GmbH & Co. KG v EUIPO dealt with a registered trademark for the design of the Rubik's Cube (No. 162784), which is owned by Seven Towns Ltd. The mark consists of a 3D rendition of the Cube, showcasing the grid pattern on all sides of the Cube. Simba Toys challenged the mark in 2006, and ultimately alleged an infringement of Article 7(1)(a) to (c) and (e) of the old Community Trade Mark Regulation (No 40/94), which set out the absolute grounds of refusal for trademark applications.

While Simba Toys put forth six arguments, the CJEU focussed only on the first, which alleged a misapplication of Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of the Regulation (which prevents the registration of a shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result), under which the General Court deemed that the essential characteristics of that shape do not perform a technical function of the goods at issue.

The CJEU first had to identify what the essential characteristics of the mark are, and the Court followed the General Court's rationale, setting them out as "...a cube and a grid structure on each surface of the cube". The essential characteristics then have to be assessed in the light of the technical function of the actual goods concerned, i.e. a three-dimensional puzzle. This has to be done using the representation given in the application, namely the drawing of the Cube, along with any descriptions of the same.

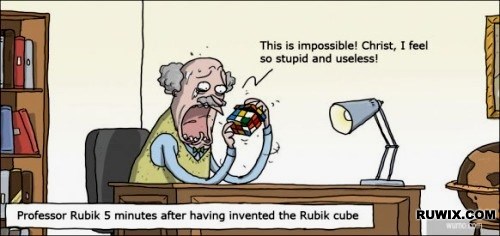

|

| Solving a Rubik's Cube can be just as challenging as protecting it |

What the CJEU therefore was concerned about was that these 'hidden' features could be used almost without limit to prohibit others from using the technical functionality of, for example, rotation for 3D puzzles, simply based on the look of the puzzle itself. This makes sense, as one can appreciate that the broadening of trademarks beyond their typical protection would mean a near monopoly on some features that are not immediately apparent based on a graphical representation. The CJEU therefore rejected the appeal, and didn't refer the matter back to the General Court.

The case sets a very important precedent, and rightsholders need to be more careful in their applications for trademarks, especially when they contain, or might contain, technical functionalities. Clearly one can appreciate the defence of legitimate trademarkable features; however, overextending your rights just might lead to the loss of your mark.

Source: IPKat